Picture this: after hours of trekking through dense Flores jungle, you round a bend and see seven conical roofs piercing through the mist like ancient stone giants. At 1,200 meters above sea level, Wae Rebo isn’t just a village—it’s a living time capsule where the Manggarai people have preserved their traditions against all odds.

This isn’t some reconstructed tourist trap; it’s a real community that earned UNESCO’s top cultural heritage award in 2012 by beating 42 global contenders 210. As modern Indonesia races forward, Wae Rebo stands as a defiantly beautiful example of how sustainable tourism can protect heritage without turning culture into a performance.

Forget Bali’s crowded beaches—this is where you come to witness a culture breathing, evolving, and welcoming visitors on its own terms.

Unveiling Wae Rebo: History and Cultural Heartbeat

Every thread of Wae Rebo’s story begins with Empu Maro, a spiritual leader who followed a vision into these mountains 18 generations ago. Oral histories say he led his people from Minangkabau in West Sumatra across seas and jungles until ancestral spirits guided him to this mist-shrouded valley. What he built was more than a settlement—it was a covenant with nature. The Manggarai philosophy of haghe (harmony) pulses through daily life here: in the rhythmic stomp of Caci whip duels at festivals, in songs thanking the forest for coffee harvests, and in the way villagers still consult shamans when children fall ill.

By the late 20th century, modernity nearly erased Wae Rebo. Families drifted to cities, and the iconic mbaru niang houses crumbled. Then in 2008, something remarkable happened. Village elders, Jakarta architects, and an NGO called Indecon launched a grassroots revival. Using salvaged wood and ancestral techniques, they rebuilt the drum houses—not as museum pieces, but as homes. When UNESCO honored them in 2012, it validated a radical idea: that cultural preservation could empower, not imprison, a community.

Architectural Marvel: The Mbaru Niang Houses

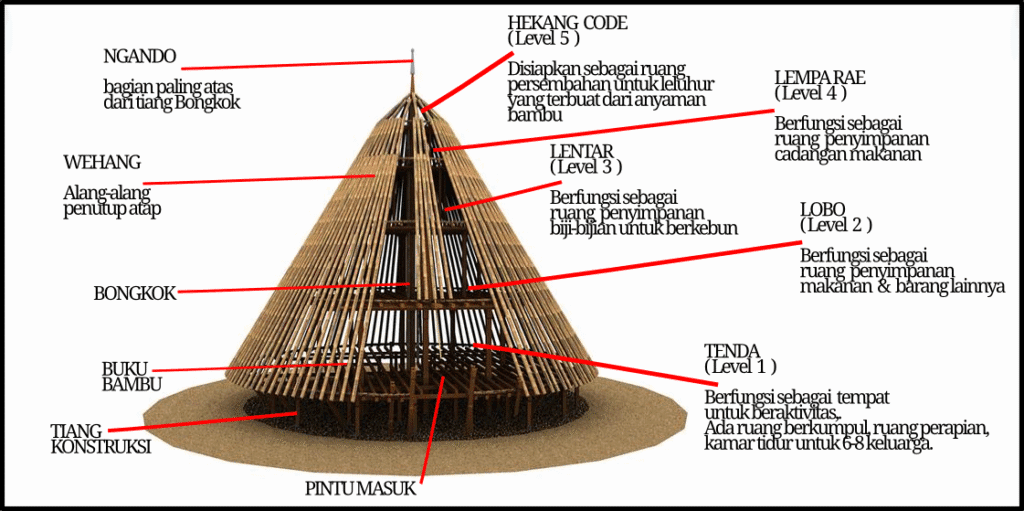

Let’s get one thing straight: calling Wae Rebo’s homes “huts” is like calling a cathedral a shed. These 15-meter-tall Mbaru Niang structures are feats of organic engineering, designed to withstand mountain gales that would flatten concrete buildings. Picture a giant cone woven from palm thatch, its roof soaring five stories high without a single nail—just interlocking timber and rattan lashings passed down through oral tradition.

But the genius isn’t just in construction; it’s in cosmology. Each level serves a sacred purpose: the ground floor (hektang kode) for family gatherings, the second (tentar) for food stores, the third (lobak) for seeds, the fourth (lempa rae) for emergency rations, and the tip (hekang kode) for offerings to ancestors. Climb the notched log ladder, and you’re ascending a vertical map of Manggarai spirituality. Seven houses encircle the compang (stone altar), representing the seven original clans—and seven mountain spirits who protect them. When UNESCO praised the 2011 restoration, they weren’t just applauding architecture; they honored a 3-month ritual where elders sang to the forest while harvesting materials, and teens learned to split bamboo with their teeth.

The Journey There: Adventure Logistics

Getting to Wae Rebo isn’t a commute—it’s a pilgrimage. From Labuan Bajo (gateway to Komodo dragons), you’ll spend 6-7 hours in a 4WD, bouncing past spiderweb rice fields in Ruteng and villages where horses outnumber cars. At Denge Village, reality hits: the last 9km are vertical. You’ll hop on a motorbike taxi ($3) to the trailhead, then start hiking.

Now, about that trek. The path climbs 1,250 meters through rainforest so lush, you’ll half-expect dinosaurs. It’s 3-4 hours of mud, sweat, and epiphanies: drinking from vines, spotting orchids clinging to ferns, and pausing at Pocoroko viewpoint—your last phone signal spot—to see the Savu Sea glittering below. Hire a porter ($15) if your backpack feels like a boulder; they’ll carry it barefoot while telling stories about forest spirits.

Pro tip: Come during the dry season (May–September). I learned this the hard way in January 2025, when landslides closed the village for two months. Nights dip to 10°C—pack that fleece!

Immersive Experiences: Living the Wae Rebo Way

Your arrival isn’t check-in; it’s ceremony. Tribal chief Papa Alex, his face a roadmap of wisdom, will chant over betel nuts while drumming echoes from the mbaru niang. Hand him $1–$2 wrapped in leaves—an offering to ancestors—and suddenly you’re family.

Days here unfold to nature’s rhythm. At dawn, join Maria in her garden to harvest colo (taro), then pound coffee beans with a wooden pestle. By afternoon, you might be weaving songket textiles in geometric patterns older than Machu Picchu, or learning why every roof beam must face north (to honor the mountain spirit).

Come dinner, gather cross-legged around the hearth. Plates don’t exist—banana leaves hold steaming cassava, wild-boar stew, and wajik (honey-taro chips). As firelight dances on carved gongs, someone starts a harvest song. “Do not forget the drum,” they sing. “It is from your ancestors”.

Then, the magic hour: when generators shut off at 10 PM, 5,000 stars punch through the blackness. Lie back on the bamboo platform, listening to frogs harmonize with snores from eight families sharing your house. This isn’t glamping; it’s time travel.

Sustainable Tourism: Balancing Culture and Commerce

Wae Rebo’s elders run tourism like village elders—wisely. Your $24/night fee funds pensions for elders, university scholarships, and that new school replacing heart-wrenching goodbyes when seven-year-olds left for distant towns 15. Coffee sales (try the organic Robusta) and $10 handwoven bracelets add income, but beds are capped at 50 to prevent Disney-fication.

Yet challenges simmer beneath the serenity. Some tourists treat it like a photo safari—drones buzzing over rituals, kids showered with candy that rots teeth (no dentists here). One mother told researchers, “Tourists spin our children until they vomit, then we carry them to the shaman”.

The solution? Visit like a guest, not a consumer. Ask before photographing faces, bring pencils instead of lollies, and linger for stories. As Martin, a guide whose family has lived here 20 generations, told me: “We rebuilt these houses not for you, but for our grandchildren. Your visit helps them remember”.

Practical Guide: Essentials for Visitors

Pack light but smart: hiking boots (trails get slick), thermal layers (yes, Indonesia has cold!), a headlamp for midnight bathroom runs, and IDR 300,000 cash (no ATMs for miles). Gifts? Skip candy—teachers beg for notebooks and pens for Denge’s school.

Accommodation is basic but profound: you’ll sleep on foam mats in a drum house loft, sharing blankets with fellow travelers. Bucket baths with icy spring water? Consider it an adrenaline rush.

Most book 2D/1N tours from Labuan Bajo ($100–$150), covering transport, meals, and guides. I used Green Rinjani Tours—their local guides know which plants cure fevers.

Beyond the Village: Flores Synergy

Pair Wae Rebo with Flores’ other wonders. En route, stop at Cancar’s spiderweb rice fields—a 500-year-old fractal agriculture system 2. Post-trek, hit Repi Beach for snorkeling before returning to Labuan Bajo to board a Komodo National Park liveaboard.

Ethical note: Avoid mass tour boats. Book through Maika Komodo (Manggarai-owned) or IndonesiaJuara—they hire Wae Rebo porters.

Conclusion: Guardians of the Clouds

Wae Rebo isn’t frozen in amber—it’s a culture choosing what to carry forward. As young men in football jerseys pound sacred drums, and solar panels charge phones beside ancestral altars, you realize: this is heritage evolving on its own terms.

The villagers’ message isn’t “Don’t come.” It’s “Come properly.” Hike the trail slowly. Taste the bitter coffee. And when Papa Alex clasps your hand at dawn, whispering “Terima kasih” (thank you) for respecting his world, you’ll feel the weight of that privilege. Take nothing but photos; leave nothing but gratitude.